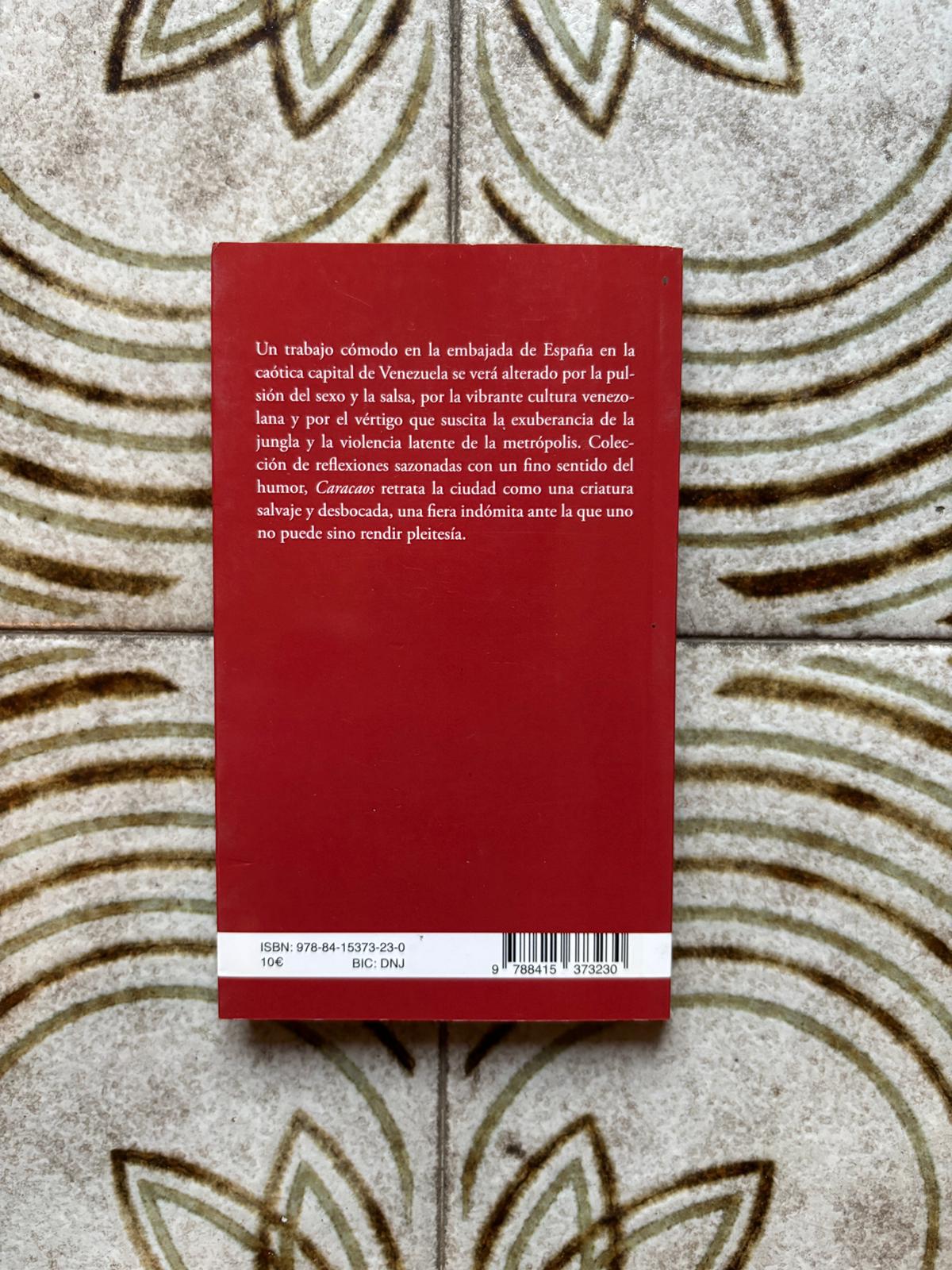

Caracaos (2015)

Title: Caracaos / Caracaos : Publisher: Melusina / City: Barcelona / Year: 2015

With that or interleaved. That or of astonishment. Or of eye. Somewhere I read that in Phoenician the o means eye. CaracaOs. Therein lies the difference, in that o that is also the indiscreet eye of Marc Caellas embedded in the Caracas that we all know, or rather, that no one knows for sure, of which we have no fucking idea.

“It is easier to understand a monster than the opposite of a monster”, says Marc Cioran. And an exploration of Caracas involves making friends or dialoguing with its monstrous condition. And like all monsters, this one does not lack tenderness, nor naivety; he has love to spare. Like adolescents, acne sprouts all over her, she also sprouts sweetness, and we feel like complimenting her when she passes by or when we pass by her in spite of her pimples, her excess of mascara and her lack of good sense.

Caracaos is a travel diary, an anthropological attempt, a book of stories, a book of chronicles, a tourist guide, a notebook, a compilation of quotations, an arbitrary discography. And in the middle of all that, as if crossing it from east to west, the experience as protagonist, as axis, the experience as the very Güaire river that together with all its shit and all its wildness crosses the city from one end to the other. The staging of the foreign experience, a mimetized foreignness that left the comfortable stalls of the Spanish embassy with its blue-eyed pitiyanki oligarch look to go to that urban circus, that concrete jungle where there are wild beasts, of course.

That’s what Héctor Lavoe says in Juanito Alimaña, but Marc puts it in Catalan translated into Venezuelan and makes salsa a presence in the book, perhaps because salsa is also a mixture, a chaos, or because there is no way to understand that city that resists knowledge without the help of Eddie Palmieri pounding the keyboards or Ray Barreto breaking the skins. By the way, once I finish reading these paragraphs and someone brings out the rum and someone else plays music, we will enjoy Marc Caellas’ performance in tropical rhythms after having burned for several years the Caracas dance floors.

Immersion. That word must be emphasized in this book. Immersion in the nets of that hedonistic chaos to represent the experience on the stages of unconventional theaters like the old house of Pérez Jiménez in the Country Club, or the room of a Hotel with Jacuzzi, or the room of a filthy hotel, or in a car flying towards the Gran Sabana while Massive Attack roars, or in El maní es así, in a table of El maní es así next to a bottle of rum. These are the scenarios of this staging of the immersion proposed by Caracaos.

Whether it is all real or all fiction, or what the proportions of one thing and the other are, does not matter. At least in this book it does not matter. Writing is a way of lying by telling the truth and of being sincere with the lie. Even he who tells the truth and nothing but the truth lies, and he who pretends to convince us that everything he writes is fiction also lies. The real truth is in the urgency of words. And the urgency of Caracaos is in the words that its author articulates and throws to compose his book, either by copying an epigraph, telling us a story, elaborating a reflection or giving us a poem or a photo. All this, apparently chaotic, is the natural habitat of this book, and at the same time an attempt at urban simulacrum. That is why Caracaos is a formal artifact, in spite of making every effort not to appear to be so, it is a formal artifact.

It is not a simple anecdote book. It is true that the whole book is full of anecdotes, of that self-fictionalized, self-faked, self-pitying self getting into trouble and playing to fill the backpack with various mundologies. But those anecdotes are permanently dislocated by the question: How the hell do I tell this story, with what narrative resources, with what aesthetic tools can I approach those memories, that memory. How to crystallize in words what experience offers us in the flesh. In the book there is not a single reference, at least explicitly, about this matter, but reading it one wonders these things, perhaps because books of experiences are in turn incessant reflections about memories, how they adhere to our lives, how they vanish or how they change.

The theme of meat is important in Caracaos. It is a carnivorous book because it deals with bodies, with the love of bodies, with skin, with the bed, with fucking, sucking, moaning. And above all of the fantasies that we insist on cultivating with all these things. There is a celebration of love, and it could not be otherwise, because there is no other way to get to know a city than fucking it. You may wonder: how is it to fuck a city? Well, you will have to read the book to find out.

On the cover is the famous photo by Nelson Garrido in which Central Park bleeds as the great national menstruation of a country that is disarticulating and self-destructing. That public country is also in the book, but as a backdrop. A backdrop that would deserve a separate volume. Politics is in Caracaos, how could it not be, and there is also the exchange control and the revolution and the opposition and the thugs and the police. But all that is like sleeping the siesta, or perhaps in the form of those horrible nightmares we dream when we sleep the siesta. By the way, as a good Spaniard or Catalan, the siesta is very important for the author of Caracaos. The cultural advisors of the Spanish embassies in Latin America should promote it as part of their cultural management, as the figurehead of their cultural management in our insomniac South American countries.